Relative Freedom: A New Vision for an Old Reality

A few weeks ago I went to a well-known weekly meeting of retired Iraqi gentlemen in Amman, Jordan. The speaker was a past chief editor of a national daily newspaper; his talk was about the future of Iraqi politics and how so many commentators long for the past and wish for a return to this leader or that era instead of thinking about the future. His thesis was that past scenarios are impossible to re-play because the many circumstances which led to their existence in the first place could not possibly re-occur simultaneously. Then he spoke about the information revolution and the explosive popularity of the internet and social media and how they revolutionized social reality, and admitted it could affect the political scene but did not elaborate on how.

I made my position known about the subject; the internet opened the political scene to everyone and to all ideas without the possibility of exclusions like before. And when I explained that this means we cannot close the door on the ideas of ISIS as well as all other extremist ideologies, and that we can only punish the criminals for their crimes but we can’t criminalize the rest for associating with extremists or defending their ideologies the speaker and some others did not agree.

It seemed to me that the meeting tolerated the crimes of other terrorists, corrupt politicians and foreign backed militias but the exclusion was saved only for ISIS sympathizers. At the end of the meeting, the convener summed up his understanding of the idea, that a high degree of understanding and respect of human rights will be required in order for the idea to work, the kind of which you will find only in a liberal society such as Germany but not in perturbed Iraq.

I lived in the west long enough to observe many people practising prejudice and incriminating by association, but I rarely met anyone among Iraqis who didn’t judge the others by association, even among activists and legal experts who should really know better that guilt should follow actions, not association or intention or faith.

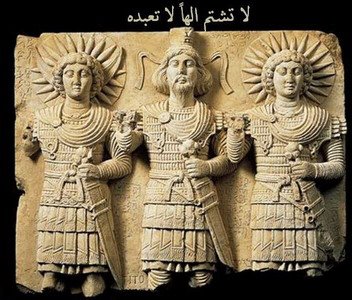

However, my expectations for the future were not based on moral or legal arguments, the kind of which may not find acceptance in present day Iraq, but on a historical observation of societal development. Iraq was the cradle for a number of religions and sub-cultures, many survived till recently, we don’t need western theorization to understand the principle of “Do not curse the god you don’t believe in”. The practitioners of disparate religions were safe in their birth place among other believers; my vision is to extend past reality to the practice of politics in the towns and villages with sympathetic majorities without over-spilling to neighbouring groups.

I am calling for relativity in defining what constitutes freedom of expression, where individuals enjoy full expression in their own territories according to local by-laws supported and protected by elected councils, not practising the same freedoms by all in every part of the country. And when I suggest ISIS defenders should have freedom of expression I am not suggesting the local police force should protect them while they spew their poison in Karbala for example, but in a hypothetical town where the elected council allows for such expressions and be responsible to defend those individuals. Relative freedom of expression should not be limited to ISIS and its defenders but includes all existing diversity of political directions and new introductions with a minimum of population and geographical areas, including those who defend Wilayet Al Faqieh, Marxists, atheists..etc.. Some may see this as a kind of federalism or decentralization or tribalism, as it may well be, but there can be no denial that it was part of the historical reality in Iraq as is evident by the continuous existence of religious and social diversity until recently. Others may object and wonder about the fate of cross-boundary aggressors; acts that are considered provocation in one sphere may not be so in another, local courts should be able to handle the differences.

There is an economic and administrative necessity to the notion of relative freedom of expression: Exclusions demand justification and security costs which only dictatorships can afford to pay, this means suppression of opposition can only be effective in the short term, with increasingly shorter term thanks to the information revolution and the breakdown of borders and controls over the spread of ideas from within and outside world societies.